Rating: 4/5 (for concept 3.5 /5 for the book as a whole)

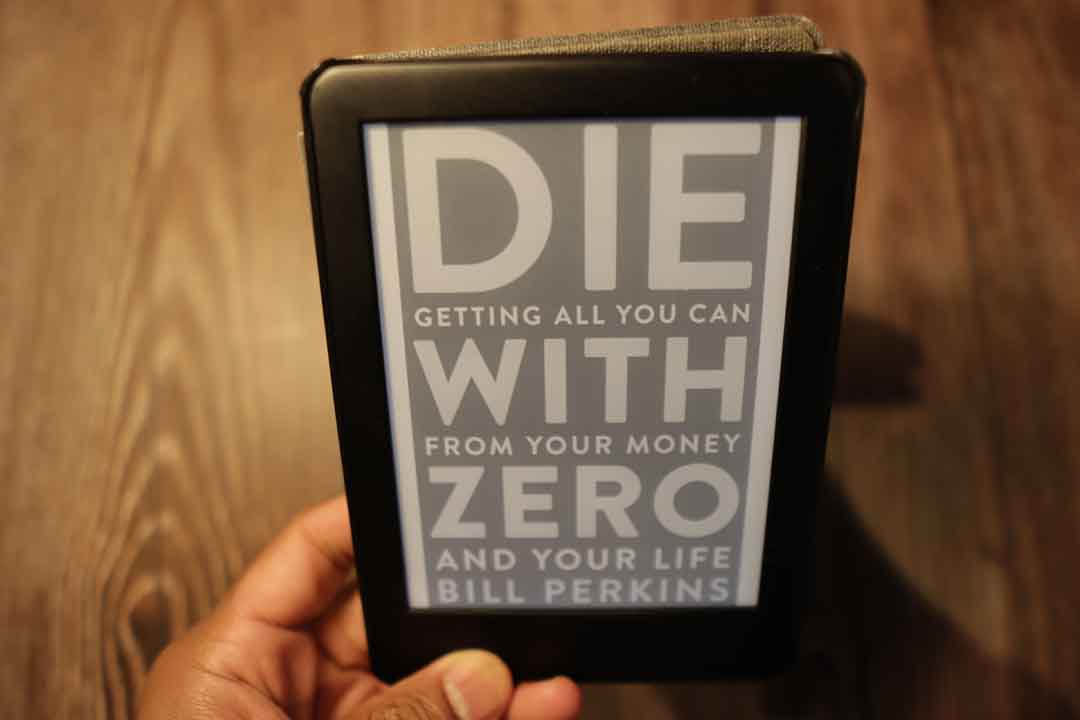

Die with Zero offers a common-sense guide to living rich – instead of dying rich

Imagine if by the time you died, you did everything you were told to. You worked hard, saved your money, and looked forward to financial freedom when you retired.

The only thing you wasted along the way was – your life.

Die with Zero presents a startling new and provocative philosophy as well as practical guide on how to get the most out of your money – and out of your life. It’s intended for those who place lifelong memorable experiences far ahead of simply making and accumulating money for one’s so-called Golden Years.

In short, Bill Perkins wants to rescue you from over-saving and under-living. Regardless of your age, Die with Zero will teach you Perkins’ plan for optimising your life, stage by stage, so you’re fully engaged and enjoying what you’ve worked and saved for.

The basic idea explored here helps you, the reader, discover how to maximise your lifetime memorable moments with experience bucketing, how to convert your earnings into priceless memories by following your net worth curve, and find out how to navigate whether to invest in, or delay, a meaningful adventure based on your spend curve and personal interest rate.

Using his own life experiences as well as the inspiring stories and cautionary tales of others – and drawing on eye-opening insights about time, money, and happiness from psychological science and behavioural finance – Perkins makes a timely, convincing, and contrarian case for living large.

For me

the groundbreaking idea in this book is “Time “Time Buckets..” Rather than having a list of to-dos where you wish to get specific things done before you pass on, Perkins proposes suggests you be intentional and divide your life in 5 to 10 year increments. Conclude what you might want to accomplish in every one of these fragments while remembering how much cash, wellbeing, and time you would require.

The idea of being deliberate with your life, your time and cash, and whom you decide to enjoy these assets with is worth reevaluating. Perkins assists you with having a less blameworthy outlook on spending your cash – to have a good time!

The idea here is to live with intention it is, indestructible the long term. Time Boxing v Time Buckets

The book can be summarised into 9 simple philosophies

1. Maximize Positive Life Experiences

2. Invest In Experiences Early

3. Aim To Die With Zero

4. Use All Available Planning Tools

5. Give Money To Kids/Charity Early

6. Don’t Live Life On Autopilot

7. Plan in Terms of Seasons

8. Know When To Stop

9. Take Big Risks Early, Not Later

Quotes and Personal Highlights.

once you’re dead, the transfer of your assets is legally enforced, and the only say you have in the matter (through your will, obviously created before you die) is where those assets get transferred. But your money is taken no matter what-so how can that be generous? The dead don’t pay taxes-only

enjoying experiences requires a combination of money, free time, and health. You need all three-money alone is never enough. And for most people, accumulating more money takes time. So by working more years to build up more savings than you actually need, you are getting more of something (money), but you are losing even more of something at least as valuable (free time and health). Here’s the bottom line: More money doesn’t equal more experience points.

This diminished enjoyment from declining health also has a real impact on how far your dollar goes, and skiing is a good example of this effect. Let’s say that an aging skier decides to continue enjoying the sport by giving himself more breaks or longer breaks between runs. Great idea-but that doesn’t mean he’s getting the same experience as when he was younger and stronger. If he used to get in 20 good runs in one day on the slopes, now he can manage only 15. In effect, the same amount of money he spent on that day of skiing now brings him only 75 percent of the skiing enjoyment it did years earlier.

To fully enjoy life instead of just surviving it, you need to stop driving mindlessly and actively steer your life the way you want it to

And so it is with all kinds of risks: The older you get, the more you have to lose. But it’s not just that the stakes are higher. The potential rewards are also lower! So even if you’re a lone wolf, or your kids are grown and flown, the risk/reward balance still isn’t in your favor when you’re older.

That is, once you have enough money to take care of your family’s basic needs, then by going to work to earn more money, you might actually be depleting your kids’ inheritance because you are spending less time with them! And the richer you already are, the more likely this is to be true.

Because that goal will have done its real job, of pushing you in the right direction: By aiming to die with zero, you will forever change your autopilot focus from earning and saving and maximizing your wealth to living the best life you possibly can. That’s why dying with zero is a worthy goal-with this goal in mind, you are sure to get more out of your life than you otherwise would have. Millions

So many people tell themselves that they are working for their kids-they just blindly assume that earning more money will benefit their kids. But until you stop to think about the numbers, you can’t know whether sacrificing your time to earn more money will result in a net benefit for your children.

Every day, a new technological advancement happens that improves lives, and over time these advances make a huge difference. But you can’t just wait for these things to happen-you have to give what you can based on the resources you have today and the resources you expect to have in the future.

Recommendations Consider at what ages you want to give money to your children, and how much you want to give. The same goes with giving money to charity. Discuss these issues with your spouse or partner. And do it today! Be sure to consult on these matters with an expert such as an estate planner or a lawyer as well.

Recommendations Think about your current physical health: What life experiences can you have now that you might not be able to have later? Think of one way in which you can invest your time or your money to improve your health and thereby improve all of your future life experiences. Learn about how to improve your eating habits to improve your health. Of the many books on this subject, the one I know well and always recommend is Eat to Live, by Joel Fuhrman, M.D. Do more of the physical activities that you already enjoy (such as dancing or hiking) that will also improve your enjoyment of future experiences. If your ability to enjoy experiences is more constrained by time than by money or by health, think of one or two ways you can spend some money now to free up more of your time.

Recommendations Calculate your annual survival cost based on where you plan to live in retirement. Consult your doctor to get a read on your biological age and mortality; get all the objective tests you can afford that give you the status of your current health and eventual decline. Given your own health and history, think about when your enjoyment of those activities is likely to start declining in a noticeable way on an annual basis-and how the activities you love will be affected by this decline.

Now suppose you’re 80. At this point, delaying an experience becomes much more costly, so your x would have to be much higher than when you were 20. Even if someone paid you 50 percent of the price of the trip to delay it, you should not necessarily take the offer-your personal interest rate at age 80 may be higher than 50 percent. It might even be higher than 100 percent. What happens if you are terminally ill? Once you know that you won’t be around a year from now, your personal interest rate is off the charts-there is no amount of money someone can pay you to delay a valuable experience. So your personal interest rate rises with age, but unfortunately we don’t always act as if it does. If this concept of a personal interest rate works for you, though, then keeping it in mind when you are considering buying an experience can help you decide whether it’s worth it to spend the money now or to save it for another time.

That’s because whenever you interact with someone, sharing an experience you’ve had, that is an experience in itself. You’re communicating, laughing, bonding, giving advice, helping them, being vulnerable-you’re doing the stuff of everyday life. By having experiences, you not only live a more engaged and interesting life yourself, but you also have more of yourself to share with others.

So your life is the sum of your experiences. But how do you maximize the value of your experiences in order to make the most out of your one life? Or, as I put it earlier in this chapter: What’s the best way to spend your life energy before you die? This book is my answer to that question.

Let me say that again: We are solving for your total life enjoyment. That is, the premise of this book is that you should be focusing on maximizing your life enjoyment rather than on maximizing your wealth. Those are two very different goals. Money is just a means to an end: Having money helps you to achieve the more important goal of enjoying your life. But trying to maximize money actually gets in the way of achieving the more important goal. So always keep this end goal in mind. Make “maximize total life enjoyment” your mantra, using it to guide every decision-including what to focus on with your financial adviser. If you tell your fee-only financial adviser that you are trying to get as much enjoyment out of your savings as possible without outliving your savings, they can help you create a plan for making that happen. The part of that plan that I’ve been focusing on in this chapter is how to avoid running out of money-how not to outspend your savings. But of course that’s just one half of the question of how to die with zero; the other half is how not to waste your life energy by underspending. So what’s the plan for spending down your money so you don’t die with leftover assets and a pile of regrets? In the language of financial advisers, how should you plan to “decumulate” the money you’ve been accumulating over the years? My full answer to that question comes in chapter 8, “Know Your Peak,” but let me just give you a brief preview here. It starts with tracking your health so you know when to start spending more than you are earning (when to crack open your nest egg). It also means knowing your projected death date and your annual cost of just staying alive, because those two numbers together tell you the bare minimum amount you will need between now and the end of your life. All your savings beyond that amount is money you must aggressively spend down on experiences that you enjoy. I say “aggressively” because your declining health and diminishing interests mean that your list of activities will narrow as you age, which means that your spending rate won’t remain constant: If you want to die with zero and make the most of whatever health you have at every point in your lifetime, you will need to spend more in your fifties than in your sixties, and more in your sixties than in your seventies, let alone your eighties and nineties! Chapter 8 further explains these ideas and gives you tools for implementing them, by yourself or with the help of a financial adviser. Final Countdown

Why spend all this money on furniture that you don’t get to enjoy?

But I don’t mean it in a schmaltzy, best-things-in-life-are-free way. In fact, the best things in life aren’t actually free, because everything you do takes away from something else you could be doing.

I have never seen somebody’s total net worth posted on their tombstone.

It’s like the song “Cat’s in the Cradle.” The lyrics are just heartbreaking: The man telling the story basically missed his son’s whole childhood, because there were always “planes to catch and bills to pay.”

The value of time with your kids is like the value of water-if you’ve got 50 gallons of water, you wouldn’t pay a dime for an additional gallon of water. But if you’re dying of thirst in the desert, you might be willing to cut off your arm to get even one gallon. Most of us, of course, are somewhere between these two

It was a life-changing moment-it just cracked my head open to new ideas about how to balance your earnings with your spending. I didn’t know it at the time, but what Joe Farrell was talking about is actually a pretty old idea in finance and accounting. It’s called consumption smoothing. Our incomes might vary from one month or one year to another, but that doesn’t mean our spending should reflect those variations-we would be better off if we evened out those variations.

The purpose of money is to have experiences, and one of those experiences for your kids is time with you. Therefore, if you are earning money but not having experiences with your kids, you are actually depriving your kids. And yourself.

The main idea here is that your life is the sum of your experiences. This just means that everything you do in life-all the daily, weekly, monthly, annual, and once-in-a-lifetime experiences you have-adds up to who you are. When you look back on your life, the richness of those experiences will determine your judgment of how full a life you’ve led. So it stands to reason that you should put some serious thought and effort into planning the kinds of experiences that you want for yourself. Without that kind of deliberate planning, you’re bound to just follow our culture’s well-trodden, default path through life-to coast on autopilot. You’ll get to your destination (death) but probably without having the kind of journey you would have actively chosen for yourself.

So your personal interest rate rises with age, but unfortunately we don’t always act as if it does. If this concept of a personal interest rate works for you, though, then keeping it in mind when you are considering buying an experience can help you decide whether it’s worth it to spend the money now or to save it for another time.

So spend your money while you’re alive-whether it’s on yourself, your loved ones, or charity. And beyond that, find the optimal times to spend money.

chances are you’re earning more per hour than you’ve ever earned before. But remember that your goal isn’t to maximize wealth but rather to maximize your life experiences. That’s a big turnabout for most people.

So before you quit or scale back your job, really think through what you want to do once your work won’t be taking up much of your everyday time. Is there a long-dormant hobby you want to pick up again? A particular friendship you want to rekindle? A new skill you want to learn, or a club you want to join? What adventures do you really want to have-and when do you want to have them? Put those in the appropriate buckets and start making new memories.

gave to educational causes, which is particularly interesting for our purposes, because the benefits of investing in education are so well documented. The benefits accrue not just to individual students (who, as a result of education, can get better jobs and enjoy better health) but also to society as a whole. Lower rates of poverty and lower rates of crime and violence are just the most obvious social benefits of education. Economists have also tried quantifying the return on investment in education, finding that, worldwide, the social returns to schooling at the secondary and higher education levels are above 10 percent (per year).

That’s why I have absolutely no regrets about the insane amount of money I spent on that one week-nor the fact that I didn’t wait

Back in the 1950s, an economist named Franco Modigliani, who went on to win the Nobel Prize, posited something that came to be known as the Life-Cycle Hypothesis (LCH)-an idea about how people manage their spending and saving to try to get the most from their money across their life span. He basically said that making the most of your money in the course of your life requires that, as another economist put it, “wealth will decline to zero by the date of death.” In other words, if you know when you will die, you must die with zero-because if you don’t, you are not getting maximum enjoyment (utility) from your money. And what about the very real possibility that you don’t know when you’ll die?

Every group already does this to some extent, though I believe they often get the magnitude wrong. Specifically, young people exchange their abundant time for money, sometimes to a fault-they should prize their free time more than most do. Old people spend a lot of their money trying to improve their health or to at least fight disease. People in the middle years sometimes

“the latte factor.” So many people stop every day for a cup of gourmet coffee-and when they do, they barely realize that the cost of all those small indulgences adds up to a lot of money in the course of a year. I’m not here to tell you to skip your daily coffee so you can save up that money to “finish rich”-in

it is much smarter to spend your healthcare money on the front end (to maintain your health and try to prevent disease) than to spend it at the end, when you get a lot less bang for every buck you spend.

The sooner you give money to medical research, for example, the sooner that money can help combat disease-as

As a result of his hard work, he will live to see another year, but he is so preoccupied with survival that he doesn’t get to enjoy summer and thrive. Neither extreme optimizes for lifetime fulfillment. Understanding that moral is one thing, but putting

Recommendations If you’re still concerned and resisting the idea of dying with zero, try to figure out where this psychological resistance comes from. If you love your job, and you love going to work every day, identify ways that you can spend your money on activities that fit your work schedule.

Right around this time, I came across an important and influential book: Your Money or Your Life, by Vicki Robins and Joe Dominguez. That book, which I’ve reread several times since-and which, about 25 years later, is now popular with a new generation of readers, many of whom are part of the FIRE movement (“financial independence, retire early”)-completely

To fully enjoy life instead of just surviving it, you need to stop driving mindlessly and actively steer your life the way you want it to go.

Let me say that again: We are solving for your total life enjoyment. That is, the premise of this book

Recommendations Remember that “early” is right now. Of those experiences you thought about earlier, think about which ones would be appropriate to invest in today, this month, or this year. If you’re resisting having them now, consider the risk of not having them now. Think about the people you’d like to have experiences with-and picture the memory dividends you stand to gain from having those experiences sooner rather than later. Think about how you can actively enhance your memory dividends. Would it help you to take more photos of your experiences? To plan reunions with people you’ve shared good times with in the past? Compile a video or a photo album?

Recommendations Identify opportunities that you’re not taking that pose little to risk to you. Always remember that you’re better off taking more chances when you are younger than when you’re older. Look at the fears that are holding you back, rational or irrational. Don’t let irrational fears get in the way of your dreams. Realize that at every moment you have a choice. The choices you make reflect your priorities, so be sure you’re making those choices deliberately.

“the annuity puzzle.” So am I telling you to go plunk down all your savings in an annuity? No, of course not. But what I am saying is that there exist solutions to the problem of how to die with zero without running out of money, and you’d be doing yourself a disservice if you didn’t at least look into them.

The longer you let the investment grow, the more money you end up with-so after a number of years, your principal ($100, for example) could double (to $200) or even triple (to $300). The real interest rate varies, but let’s take the example of 8 percent annual growth. (That is a little more than the average stock market return since its inception-again, after adjusting for inflation.) At that rate, your $100 becomes $147 in five years. In ten years, it becomes $216-more than enough to buy two of whatever experience you thought about buying now. The question is: Should you wait nine to ten years to get two of the experiences you could have today? It’s totally up to you,

Recommendations If time-bucketing your whole life feels a bit overwhelming, just do the exercise with three time buckets covering the next 30 years. Know you can always add more to your list; just do it long before your age and health become a real factor.

Think, for example, of the amazing gift Robert F. Smith gave to the class of 2019 of Morehouse

Travel is a good example: To me, travel is the ultimate gauge of a person’s ability to extract enjoyment from money, because it takes time, money, and, above all, health. Many 80-year-olds just can’t travel much or far-their health prevents it. But you don’t need to be completely debilitated to want to avoid some of the hassles

But don’t get me wrong: I am not an advocate for everyone spending their savings on travel, let alone poker. What I am an advocate for is deciding what makes you happy and then converting your money into the experiences you choose.

Warren Buffett and other investment advisers are trying to grow money, and I’m trying to grow the richest life I can; and when I say rich, I mean rich in experiences, in adventures, in memories-rich in all the reasons you acquire money. So here’s my investment advice in a nutshell: Invest in your life’s experiences-and start early, start early, start early. Now, you might be saying, how can you expect me to invest in experiences early in life when I’m broke?

enough-many people live as if they forget that this is the point of earning, saving, and investing money.

It’s a harsh reality: Your health just keeps declining from your peak years in your late teens and twenties, sometimes suddenly but usually so gradually that you don’t notice it. When I was young, I loved playing sports, especially football. I still like football-but even as a healthy 50-year-old, I can’t possibly enjoy it as much as I did when I was 20. I can’t run as fast, and I’m much more prone to injuries.

you should be focusing on maximizing your life enjoyment rather than on maximizing your wealth. Those are two very different goals.

Think, for example, of the amazing gift Robert F. Smith gave to the class of 2019 of Morehouse College, paying off all their student loans. Whatever his motives were, whatever amount his gift added up to, the point is that Smith didn’t put it in his will-he gave while

Remember: In the end, the business of life is the acquisition of memories.

Consider this headline, above one of the most emailed New York Times stories in the week it came out: “96-Year-Old Secretary Quietly Amasses Fortune, Then Donates $8.2 Million.” Wow! The story explained how a Brooklyn woman named Sylvia Bloom managed to amass so much wealth on her salary as a legal secretary. Though she’d been married, she had no children, and she worked for the same Wall Street law firm for 67 years, lived in a rent-controlled apartment, took the subway to work even into her nineties-and made her savings grow by replicating on a smaller scale the investments made by the lawyers she worked for. Nobody close to Ms. Bloom had any idea of her wealth until after her death. She made a bequest of $6.24 million to a social service organization called the Henry Street Settlement; another $2 million went to Hunter College and a scholarship fund.

In other words, to get the most out of your time and money, timing matters.

Learn from Your “Time Buckets” Time buckets are a simple tool for discovering what you want your life to look like in broad strokes. Here’s what I suggest you do. Draw a timeline of your life from now to the grave, then divide it into intervals of five or ten years. Each of those intervals-say, from age 30 to 40, or from 70 to 75-is a time bucket, which is just a random grouping of years.

Think about it: If your parents took you along on a tour of Italy when you were a toddler, how much did you get out of that expensive vacation, besides maybe a lifelong love of gelato? Or consider the other extreme: How much do you think you’ll enjoy climbing Rome’s Spanish Steps when you’re in your nineties-assuming you’ll still be alive and able to climb them at all by then? As the title of one economics journal article put it, “What Good Is Wealth Without Health?”

You can’t delay everything, but you can delay some things. I do believe firmly that your real legacy

Death wakes people up, and the closer it gets, the more awake and aware we become.

I like to maintain a certain body weight, so when I look at a cookie, I convert it to time on the treadmill. Sometimes, when I see a cookie that looks good, I’ll take a bite to see how good it tastes and then ask myself, Is eating this cookie worth walking an extra hour on the treadmill?

people forget those costs of acquiring more money, so they focus mainly on the gains. So, for example, $2.5 million does buy you a better quality of life than $2 million, all other things being equal-but all other things are usually not equal! That’s because for every additional day you spend working, you sacrifice an equivalent amount of free time, and during that time your health gradually declines, too. If you wait five years to stop saving, your overall health declines by five years, closing the window on certain experiences altogether. In sum, from my perspective, the years you spend earning that extra $500,000 do not make up for (let alone surpass) the number of experience points you lost by working for more money instead of enjoying those five years of free time.

So how do you quantify such things-what is the value of a positive memory? Your first instinct might be to say that it’s impossible to say, or that memories are priceless. But let me put it another way: What is the value to you of a week at a cabin on a lake? Or of a day with a beloved relative? The price might be extremely high or fairly low, but the fact that you can even propose a ballpark price says that the value of an experience can be quantified. (In fact, you might recall doing that with “experience points” in an earlier chapter.)