When we met, she smiled as soon as she saw me. A warm, inviting smile. It’s the kind you might see when a primary school teacher greets her class in the morning. It felt like an olive branch of safety. Something unforced. Unperformed. Real. Before any question had even landed, she’d already set the tone. This is because; First impressions really do count.

Our conversation began with something simple, almost ordinary: a reminder that “People are People.” But the way she said it carried weight, like a phrase she’d repeated to herself through long stretches of uncertainty. I’ve heard that line before, first from my grandad, then from my dad. I heard it so often that it became a small mantra between my brother and me, especially when life goes wrong and it’s tempting to blame one person for everything: people are people.

She didn’t know any of that. But hearing her say it, so casually and sincerely, felt like my first thoughts were being reaffirmed. I’ll call her Lisette. She’s from Colombia, and she has been living in the Netherlands a little over a year.

She is also a mother of two.

Her eldest child is her son, born from a previous relationship. When she speaks about him, her voice softens in a different way calmer, steadier. They talk regularly, staying closely connected despite the distance. Her relationship with her daughter, however, is far more complicated and deeply painful.

The child was born during a later relationship. The same relationship that ultimately forced Lisette to leave Colombia. She told me that the father fabricated a kidnapping story in an attempt to pressure her into returning. When that failed, he severed contact between mother and daughter.

Not long after, the situation escalated further. Lisette described repeated threats to her life, connected to the same man and his influence. What began as emotional manipulation turned into something far more dangerous. It became clear that staying in Colombia was no longer safe. Not for her, and not for the future she wanted to protect for her children.

Leaving meant choosing survival, but it also meant separation.

Today, Lisette has no direct contact with her daughter at all. It’s a loss that doesn’t come with closure. One she carries quietly.

She told me this is something she has been working through in therapy with her psychologist (someone she credits as an important part of her healing process). Still, she described it as an internal pain that doesn’t disappear. It’s something you learn to live alongside, she said, because life continues to move forward whether you are ready or not.

Much of her journey since leaving Colombia has been about learning how to remain emotionally present as a mother, even when forced distance has made that role more complicated.

There’s a particular steadiness you notice in someone who has had to rebuild their life quickly. Lisette speaks with warmth and openness, and then, without warning, her voice softens, quietens. It’s the tone people use for experiences that still sit close to the surface. She didn’t come to the Netherlands for adventure or opportunity in the usual sense. She came for protection.

When I asked if she felt comfortable sharing her journey, she paused. Not because she couldn’t speak, but because she was measuring what it costs to tell the truth out loud, to a stranger. To me.

That moment always feels delicate on my side, too. I don’t know what her first impression of me is. I know I’m asking for a lot, with little to nothing I can offer in return. All I can really do is try to make it clear: she’s in safe hands, and she’s in the driving seat. I’m the passenger holding the map. The questions on my laptop, the structure of the conversation are a guide for where she chooses to go.

I didn’t sense hesitation so much as caution. To ease into it, I told her Colombia is beautiful, and asked if I could show her a little of the work I’d done there in Colombia : interviews, photos, fragments of other stories. Instantly, the smile came back. I traced my route on the screen: starting in the Caribbean north and moving down through the country. She recognised places I’d been. She paused on a photograph, smiled again, and then, she gently and slowly, answered the question.

In Colombia, she said, her life became unsafe. She described an ex-husband connected to law enforcement and corruption. What followed were threats and fear that didn’t stay contained to private conflict. She referenced pressure involving her child and multiple attempts on her life. It’s the kind of danger that doesn’t isolate itself to one person; it moves through a family like an electrical current. It leaves everyone tense, watchful, exhausted.

She didn’t linger on details. And I didn’t push. Vulnerability has its own boundaries. But the message was clear: she reached a point where staying no longer felt possible.

“There was too much trouble,” she told me. “My life is better here.”

Lisette arrived with a small amount of luggage. A cabin bag only. Its the kind of detail that doesn’t sound important until you imagine what it means. To leave with only what you can carry is to accept you might not come back. It’s a kind of grief that doesn’t always look like tears; sometimes it looks like practical decisions made in a hurry, a life condensed into a phone, a few documents, and whatever fits into a carry-on.

She had a personal connection in the Netherlands. She had someone who could helped her land in a place where she wouldn’t be alone from the first day. That thin thread mattered. Often, survival isn’t about grand plans. It’s about one person who answers a call, and a country whose system might take time, but still holds the possibility of safety.

When I asked what she liked about her new life, she didn’t reach for clichés. She talked about freedom: the absence of constant fear, the way the days can be ordinary again. The word happy came up repeatedly. Not as an exaggerated performance, but as something she still sounded slightly surprised to be able to claim.

And then we drifted into daily life and the territory where rebuilding becomes visible.

Lisette is interested in beauty work: lashes, brows, the careful craft of helping someone feel more like themselves when they look in the mirror. She doesn’t describe it as a hobby. She describes it as a future. She wants her own business, possibly her own products, her own independence. As a child, she was drawn to business; she studied with that in mind. Now, she sees beauty not as vanity, but as skill and livelihood something she can build with her own two hands.

The conversation moved the way real life does: serious, then light, then serious again.

We talked about food. She laughs as she declares her love for chicken and rice. Its then on to the small discoveries in a new country. I mentioned the way cheese appears in practically every Dutch meal, and she lit up, telling me she loves eating cheese with hot chocolate. I repeat the statement and she cant stop laughing. Salt against sweetness, comfort against cold. It’s a tiny culinary detail, but it landed like a postcard from home.

What stayed with me most, though, was her emotional intelligence and the way she was willing to show it. Lisette describes herself as sensitive to “energy.” She notices when someone feels heavy. She feels it in her own body. Sometimes sadness comes, and she has to goes to her room to cry. she tell me that It will last for an hour, maybe two or until she feels “finished.” then like a Caribbean storm, it passes through and leaves her able to continue.

It isn’t denial. It’s a method of surviving.

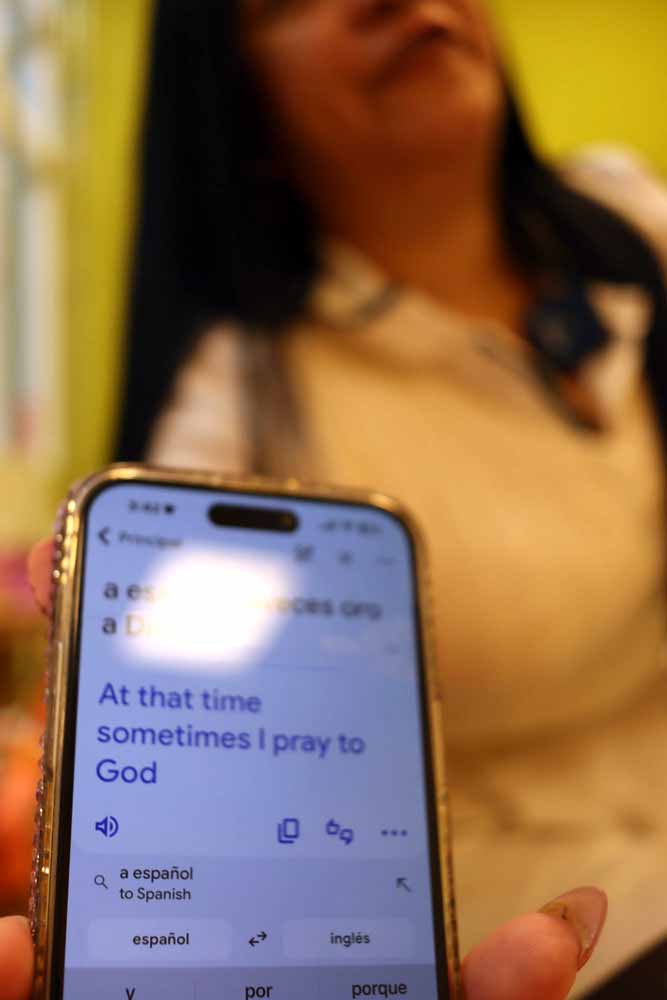

At one point, I mentioned how the idea of pain moving through you, like water, reminded me of the Christian imagery of baptism. Then I asked if she believes in God.

Her answer surprised me in its simplicity: faith is part of life.

Lisette prays every day. She speaks about God without preaching, more like someone describing a lifeline. In her telling, belief isn’t about rules or institutions. It’s about being held. She says she feels protected (by God, by angels, by something beyond what she can prove.) For someone who has lived with fear, protection isn’t abstract. It’s physical. It’s the difference between sleeping and staying awake. Maybe that’s why she mentioned waking in the night to pray (sometimes at 3 a.m) as if to steady herself in the quietest hours.

By the end of our conversation, the core message returned: people are people.

It sounds simple again, but now it’s layered. It means: don’t reduce me to a case file. Don’t turn my story into spectacle. Don’t forget I am more than what happened to me. It means: I can be afraid and hopeful at the same time. I can be rebuilding and still grieving. I can miss home and still choose safety.

Building a new life in a new place may seem like one big leap, but in reality it’s made from thousands of small ones: one routine, one prayer, one friendship at a time.

The uncertainty is still very real. She is waiting for paperwork and doesn’t know exactly how long it will take. But she speaks about the Netherlands with unmistakable relief. Here, she says, life feels calmer.

Here, she can breathe, even if the only way she can see her daughter now is through photos on social media. It’s hard, she tells me. It reopens old wounds. But she needs to know her daughter is okay. And for now, that has to be enough.