Stealing Like an Artist

A student, Trent, from my old secondary school, recently approached me to use my work as part of an artist research project. Instead of simply sending references, I invited him and his Dad into the studio.

What followed wasn’t teaching in the traditional sense. It was closer to a conversation.

One of the hardest parts of mentoring is not placing your ideas onto someone else’s work. Trent is young (15) and so he lacks exposure the world, resources, and access to the professional world. But when you speak to him, his ideas are clear and energetic. It’s difficult to ignore someone (old or young) who asks for guidance not out of laziness, but out of curiosity and determination.

The goal of teaching is never to create a smaller version of yourself. NEVER

It is instead to help someone understand how ideas form, how they move, and how they change when they pass through another person.

Austin Kleon describes this in one of my favourite art books Steal Like an Artist:

“creativity doesn’t come from nowhere. It comes from absorbing influences and transforming them into something personal “ not copying, but translating.

That idea became the framework for how we worked together.

A Lineage of Ideas

Art history is full of conversations across generations.

Anthony Caro studied under Henry Moore, who removed sculpture from the plinth and placed it directly into the viewer’s space.

Caro later taught Michael Craig-Martin.

Michael Craig-Martin taught Julian Opie (and we love Opie’s recent colour pallet.)

Each artist worked differently, yet the thinking connects them. The work evolves not because one replaces the other, but because each reinterprets what they inherited; a kind of visual butterfly effect.

Cubism reshaped how we see form by breaking objects into multiple viewpoints.

Later movements: Dada, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism – then responded to changing culture, technology, and conflict. On the surface they appear unrelated, yet conceptually they are linked through reaction and reinterpretation.

Originality is not isolation.

Originality is continuation.

So when Trent showed me his artist study based on our recent Sierra Leone pieces, he instinctively responded to it instead.

He used colour differently.

He made compositional decisions I wouldn’t make.

Yet the work still carried a familiarity.

That tension, the similarity and the difference IS where learning happens.

Physical Before Digital

In the studio we try not to begin with computers. Too much access to infinite options actually restricts ideas rather than expanding them. We therefore begin with what might simply be called common sense approach. This is because we’re not aiming for a Revolution, but rather a Revelation understanding.

[Thomas Paine’s argument in his book Common Sense was that knowledge and authority shouldn’t belong to a select few. Creative thinking works the same way, ideas aren’t owned, they’re developed.] and so So we started physically:

- Cutting paper

- Re-photographing images

- Breaking pictures apart and rebuilding them by hand

The reasoning was simple:

If you can make it physically, you understand it.

Once you understand it, the computer becomes a tool rather than a crutch.

Only after this did we translate the ideas into Code

I developed the Python systems used in the final works, but the visual direction emerged through dialogue. Think question, response, adjustment. ie more conversation than instruction.

Tools can be authored.

Ideas are exchanged.

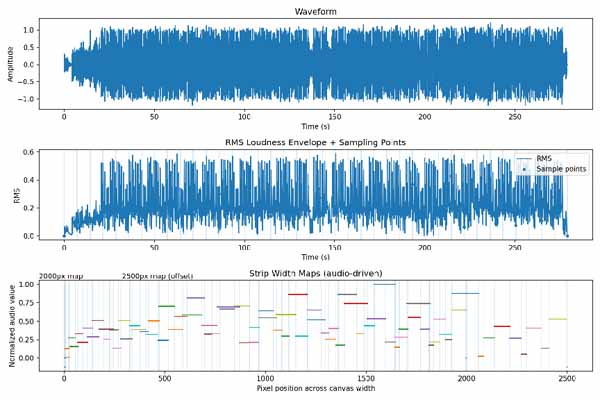

Sound as Structure

From our discussions about repetition and reconstruction, Trent began sending voice notes. The natural language of his generation. That led us to a question:

Can sound organise an image rather than decorate it?

Instead of letting audio affect colour or mood, we allowed it to control structure. Slicing an image into segments determined by the dynamics of a waveform and rebuilding it into a new composition.

The photograph remains the same.

The arrangement changes.

Different songs or individual voice notes create different visual rhythms from the same source image.

The technical framework was written by me, but the direction came from shared exploration. The work sits between independent practice and collaboration: not imitation, not delegation, but response. Trent can translate the process further toward his own project and intentions.

Influence Is Not Plagiarism

Throughout this process we discussed influence openly.

Artists influence artists.

Teachers influence students.

Students influence teachers.

Even this text is shaped through dialogue. Spoken ideas are reorganised and clarified through conversation and edits until you get what you are reading here. The authorship again remains mine but the structure emerges through exchange with others.

That is the difference between copying and working within a lineage.

Trent’s work is his because he interprets and translates through his own decisions.

Mine is mine because I build the systems and frameworks he reacts to.

Neither replaces the other, they exist within the same conversation.

Creativity isn’t ownership of a single idea.

It’s participation in an ongoing one.

Thank you for the lesson, Trent.