Rating:

5 stars

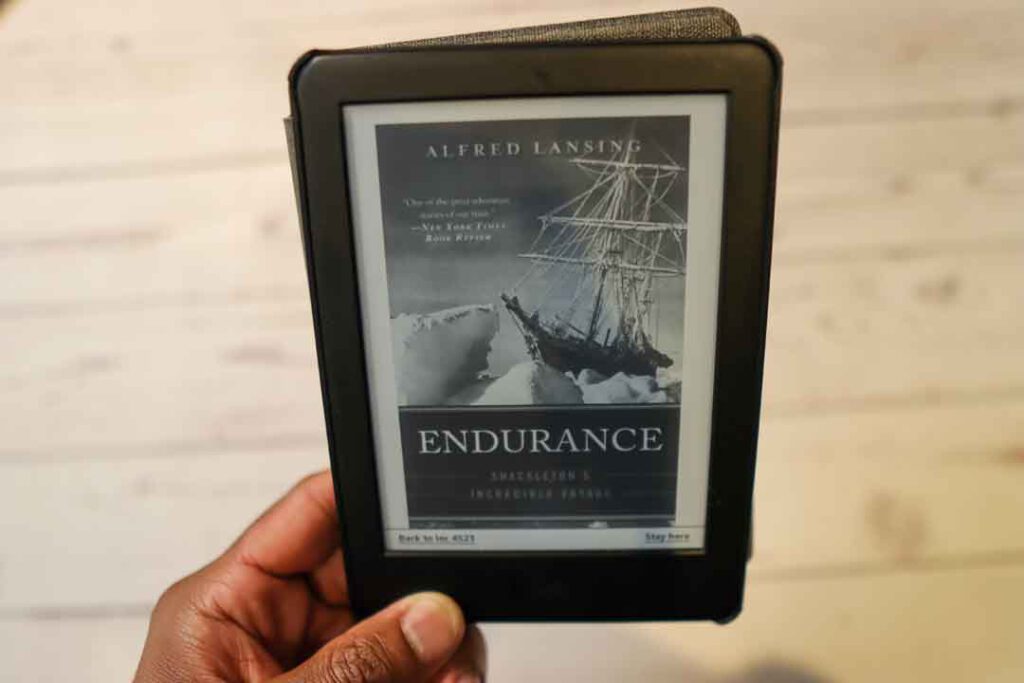

Editors Forward:

The harrowing tale of British explorer Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 attempt to reach the South Pole, one of the greatest adventure stories of the modern age.

In August 1914, polar explorer Ernest Shackleton boarded the Endurance became locked in an island of ice. Thus began the legendary ordeal of Shackleton and his crew of twenty-seven men. When their ship was finally crushed between two ice floes, they attempted a near-impossible journey over 850 miles of the South Atlantic’s heaviest seas to the closest outpost of civilization.

In Endurance, the definitive account of Ernest Shackleton’s fateful trip, Alfred Lansing brilliantly narrates the harrowing and miraculous voyage that has defined heroism for the modern age.

Favourite quotes / Highlights

No matter what the odds, a man does not pin his last hope for survival on something and then expect that it will fail.”

England. One has very few other longings for civilization-good bread and butter, Munich beer, Coromandel rock oysters, apple pie and Devonshire cream are pleasant reminiscences rather than longings.”

he dressed and went outside. He noticed that the swell had increased and their floe had swung around so that it was meeting the seas head on. He had stood watching for only a few moments, when there was a deep-throated thud and the floe split beneath his feet-and directly under No. 4 tent in which the eight forecastle hands were sleeping.

Her crew consisted of six men whose faces were black with caked soot and half-hidden by matted beards, whose bodies were dead white from constant soaking in salt water. In addition, their faces, and particularly their fingers were marked with ugly round patches of missing skin where frostbites had eaten into their flesh. Their legs from the knees down were chafed and raw from the countless punishing trips crawling across the rocks in the bottom. And all of them were afflicted with salt water boils on their wrists, ankles, and buttocks. But had someone unexpectedly come upon this bizarre scene, undoubtedly the most striking thing would have been the attitude of the men . . . relaxed, even faintly jovial-almost as if they were on an outing of some sort.

Hour after hour hey rowed, and the outline of Elephant Island slowly grew larger. At noon, they had covered almost half the distance; by one-thirty they were less than 15 miles away. They had had no sleep for almost eighty hours, and their bodies had been drained by exposure and effort of almost the last vestige of vitality. But the conviction that they had to land by nightfall gave rise to a strength born of desperation. It was pull or perish, and ignoring their sickening thirst, they leaned on their oars with what seemed the last of their strength.

In the beginning a few of the men, particularly little Louis Rickenson, the chief engineer, were squeamish about this seemingly cold-blooded method of hunting. But not for long. The will to survive soon dispelled any hesitancy to obtain food by any means.

It connects the hazardous Drake Passage with the waters of the Weddell Sea-and it is a treacherous place. It was named in honor of Edward Bransfield, who, in 1820, took a small brig named the Williams into the waters which now bear his name. According to the British, Bransfield was thus the first man ever to set eyes on the Antarctic Continent.

It is a battle against a tireless enemy in which man never actually wins; the most that he can hope for is not to be defeated.

It was now about three o’clock, and Worsley himself began to fail. He had faced the wind so long that his eyes refused to function properly, and he found it impossible to judge distance. Try as he might, he could no longer stay awake. They had been in the boats now for five and a half days, and during that time almost everyone had come to look upon Worsley in a new light. In the past he had been thought of as excitable and wild-even irresponsible. But all that was changed now. During these past days he had exhibited an almost phenomenal ability, both as a navigator and in the demanding skill of handling a small boat. There wasn’t another man in the party even comparable with him, and he had assumed an entirely new stature because of it.

It was the merest handhold, 100 feet wide and 50 feet deep. A meager grip on a savage coast, exposed to the full fury of the sub-Antarctic Ocean. But no matter-they were on land. For the first time in 497 days they were on land. Solid, unsinkable, immovable, blessed land.

On the Caird they managed to make enough room for four men to huddle together at one time in the pile of sleeping bags in the bow, and they took turns trying in vain to sleep. On the Docker, however, there was only room enough for the men to sit upright, huddled together with their feet squeezed between the cases of stores. The seas that came on board ran down into the bottom of the boat, and since most of the men were wearing felt boots, their feet were soaked all night in the icy water. They did what they could to keep the boats bailed dry, but the water sometimes rose ankle-deep. To keep their feet from freezing, they worked their toes constantly inside their boots. They could only hope that the pain in their feet would continue, because comfort, much as they yearned for it, would mean that they were freezing. After a time, it took extreme concentration for them to keep wiggling their toes-it would have been so terribly easy just to stop.

Since abandoning the Endurance, they had covered 80 miles in a straight line almost due north. But their drift had described a slight arc, which was now curving definitely to the east, away from land. Not enough to cause real worry, but enough to stir concern.

Sir I am about to try to reach Husvik on the East Coast of this island for relief of our party. I am leaving you in charge of the party consisting of Vincent, McCarthy & yourself. You will remain here until relief arrives. You have ample seal food which you can supplement with birds and fish according to your skill. You are left with a double barrelled gun, 50 cartridges [and other rations] . . . You also have all the necessary equipment to support life for an indefinite period in the event of my non-return. You had better after winter is over try and sail around to the East Coast. The course I am making towards Husvik is East magnetic. I trust to have you relieved in a few days. Yours faithfully E. H. Shackleton

The date was October 27, 1915. The name of the ship was Endurance. The position was 69°5′ South, 51°30′ West-deep in the icy wasteland of the Antarctic’s treacherous Weddell Sea, just about midway between the South Pole and the nearest known outpost of humanity, some 1,200 miles away.

The following day, a party of men were set to digging into the snow-covered refuse heap to recover all possible blubber from the bones there. Seal flippers were cut up, and the decapitated heads of seals were skinned and scraped of every trace of blubber they would yield.

The hardest part of the operation was getting the seal back to the ship, since many of them weighed 400 pounds and more. But there was always a struggle to get the job done as quickly as possible so that the seal wouldn’t cool off before it arrived. While the flesh was warm, the men who skinned and butchered the carcass didn’t get their hands frostbitten.

The period at the oars was kept short so that each man had a turn as often as possible. It was the only way to keep warm. Those who were not rowing or on lookout did what they could to keep their blood moving. But sleep was out of the question, for there was nowhere to lie down. The bottom of each boat was so packed with stores that there was scarcely room for the men’s feet. Sleeping bags and tents took up most of the space in the bows, and the two thwarts on which the oarsmen sat had to be kept free. That left only a small space midships for the off-duty men

The plan, as they all knew, was to march toward Paulet Island, 346 miles to the northwest, where the stores left in 1902 should still be. The distance was farther than from New York City to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and they would be dragging two of their three boats with them, since it was assumed that they would eventually run into open water.

The remainder of that night was an eternity, composed of seconds individually endured until they merged into minutes and minutes finally grew into hours. And through it all there was the voice of the wind, shrieking as they had never heard it shriek before in all their lives.

They would land by nightfall-provided that not a moment was lost. Shackleton, impatient to be on the move, gave the order to get underway immediately. But it was not that simple. The light of dawn revealed the results of the night. Many faces were marked by the ugly white rings of frostbite, and almost everyone was afflicted with salt-water boils that gave off a gray, curdlike discharge when they broke. McIlroy called to Shackleton from the Wills that Blackboro’s feet apparently were gone because he had been unable to restore circulation in them. And Shackleton himself looked haggard. His voice, which was usually strong and clear, had grown hoarse with exhaustion. Both the Docker and the Wills were severely iced up, inside and out. It took more than an hour to chip away enough to make them fit for sailing.

Throughout the night the men were troubled by the need to urinate frequently. Certainly the intense cold was a factor in this condition, and the two physicians believed it was aggravated by the fact that they were continually wet so that they absorbed water through their skin. Whatever the reason, it required a man to leave the slight comfort of the sheltering canvas and make his way to the lee side of the boat several times during the night. Most of the men also had diarrhea from their diet of uncooked pemmican, and they would suddenly have to rush for the side and, holding fast to a shroud, sit on the frozen gunwale. Invariably, the icy sea wet them from beneath.

To Greenstreet they looked like a pair of tin snips. Carefully, McIlroy reached well up under the flap of skin to where the toes joined the foot. Then one at a time he cut them off. Each dropped with a metallic clatter into the empty tin can below. Next McIlroy meticulously scraped away the dead, blackened flesh, and when the wound was clean, be carefully stitched it up. Finally it was done; Blackboro’s foot had been neatly trimmed off just at the ball joint. Altogether it had taken fifty-five minutes. Before long Blackboro began to

Toward eleven o’clock, Shackleton became strangely uneasy, so he dressed and went outside. He noticed that the swell had increased and their floe had swung around so that it was meeting the seas head on. He had stood watching for only a few moments, when there was a deep-throated thud and the floe split beneath his feet-and directly under No. 4 tent in which the eight forecastle hands were sleeping. Almost instantly the two pieces of the floe drew apart, the tent collapsed and there was a splash. The crewmen scrambled out from under the limp canvas. “Somebody’s missing,” one man shouted. Shackleton rushed forward and began to tear the tent away. In the dark he could hear muffled, gasping noises coming from below. When he finally got the tent out of the way, he saw a shapeless form wriggling in the water-a man in his sleeping bag. Shackleton reached down for the bag and with one tremendous heave, he pulled it out of the water. A moment later, the two halves of the broken floe came together with a violent shock. The man in the sleeping bag turned out to be Ernie Holness, one of the firemen. He was soaked through but he was alive, and there was no time to worry about him then because the crack was opening once more, this time very rapidly, cutting off the occupants of Shackleton’s tent and the men who had been sleeping in the Caird from the rest of the party.

Unlike the land, where courage and the simple will to endure can often see a man through, the struggle against the sea is an act of physical combat, and there is no escape. It is a battle against a tireless enemy in which man never actually wins; the most that he can hope for is not to be defeated.

Nevertheless, the sudden appearance of the Adélies had removed, for the moment, the most serious threat they faced-starvation. And with starvation no longer an immediate danger, their thoughts inevitably turned once more to their ultimate escape.

When it came time to haul in the sea anchor, Cheetham and Holness leaned over the bow of the Docker trying to untie the icy knot in the rope with fingers so stiff they would hardly move. While they worked, the Docker rose to a sea, then pitched downward. Holness failed to pull his head away, and two of his teeth were knocked out on the sea anchor.

Worsley returned to camp in time for breakfast, and they resumed the journey at 8 P.M. But toward eleven o’clock, after they had made nearly a mile and a half, their way was blocked by a number of large cracks and bits of broken ice. The party pitched the tents at midnight and turned in. Most of the men were soaked through-from the water in which they lay, and from their own sweat. And none of them had a change of clothes except for socks and mittens, so they were forced to crawl into their sleeping bags wearing their soggy garments.

Of all their enemies — the cold, the ice, the sea — he feared none more than demoralization.”

| Fortitudine vincimus-By endurance we conquer.” |

A forbidding-looking place, certainly, but that only made it seem the more pitiful. It was the refuge of twenty-two men who, at that very moment, were camped on a precarious, storm-washed spit of beach, as helpless and isolated from the outside world as if they were on another planet. Their plight was known only to the six men in this ridiculously little boat, whose responsibility now was to prove that all the laws of chance were wrong-and return with help. It was a staggering trust.”

And all the defenses they had so carefully constructed to prevent hope from entering their minds collapsed.”

And in the space of a few short hours, life had been reduced from a highly complex existence, with a thousand petty problems, to one of the barest simplicity in which only one real task remained-the achievement of the goal.”

Even at home, with theatres and all sorts of amusements, changes of scene and people, four months idleness would be tedious: One can then imagine how much worse it is for us.”

For scientific leadership give me Scott; for swift and efficient travel, Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when there seems no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

In all the world there is no desolation more complete than the polar night. It is a return to the Ice Age- no warmth, no life, no movement. Only those who have experienced it can fully appreciate what it means to be without the sun day after day and week after week. Few men unaccustomed to it can fight off its effects altogether, and it has driven some men mad.”

In some ways they had come to know themselves better. In this lonely world of ice and emptiness, they had achieved at least a limited kind of contentment. They had been tested and found not wanting.”

In that instant they felt an overwhelming sense of pride and accomplishment. Though they had failed dismally even to come close to the expedition’s original objective, they knew now that somehow they had done much, much more than ever they set out to do.”

It was a dramatic gesture, but that was the way Shackleton wanted it. From studying the outcome of past expeditions, he believed that those that burdened themselves with equipment to meet every contingency had fared much worse than those that had sacrificed total preparedness for speed.”

It was as if they had suddenly emerged into infinity. They had an ocean to themselves, a desolate, hostile vastness. Shackleton thought of the lines of Coleridge: Alone, alone, all, all alone, Alone on a wide wide sea.”

More than any other single impression in those final hours, all the men were struck, almost to the point of horror, by the way the ship behaved like a giant beast in its death agonies.”

Returning from a hunting trip, Orde-Lees, traveling on skis across the rotting surface of the ice, had just about reached camp when an evil, knoblike head burst out of the water just in front of him. He turned and fled, pushing as hard as he could with his ski poles and shouting for Wild to bring his rifle. The animal-a sea leopard-sprang out of the water and came after him, bounding across the ice with the peculiar rocking-horse gait of a seal on land. The beast looked like a small dinosaur, with a long, serpentine neck. After a half-dozen leaps, the sea leopard had almost caught up with Orde-Lees when it unaccountably wheeled and plunged again into the water. By then, Orde-Lees had nearly reached the opposite side of the floe; he was about to cross to safe ice when the sea leopard’s head exploded out of the water directly ahead of him. The animal had tracked his shadow across the ice. It made a savage lunge for Orde-Lees with its mouth open, revealing an enormous array of sawlike teeth. Orde-Lees’ shouts for help rose to screams and he turned and raced away from his attacker. The animal leaped out of the water again in pursuit just as Wild arrived with his rifle. The sea leopard spotted Wild, and turned to attack him. Wild dropped to one knee and fired again and again at the onrushing beast. It was less than 30 feet away when it finally dropped. Two dog teams were required to bring the carcass into camp. It measured 12 feet long, and they estimated its weight at about 1,100 pounds. It was a predatory species of seal, and resembled a leopard only in its spotted coat-and its disposition. When it was butchered, balls of hair 2 and 3 inches in diameter were found in its stomach-the remains of crabeater seals it had eaten. The sea leopard’s jawbone, which measured nearly 9 inches across, was given to Orde-Lees as a souvenir of his encounter. In his diary that night, Worsley observed: A man on foot in soft, deep snow and unarmed would not have a chance against such an animal as they almost bound along with a rearing, undulating motion at least five miles an hour. They attack without provocation, looking on man as a penguin or seal.”

The he laid the Bible in the snow and walked away.

The ship reacted to each fresh wave of pressure in a different way. Sometimes she simply quivered briefly as a human being might wince if seized by a single, stabbing pain. Other times she retched in a series of convulsive jerks accompanied by anguished outcries. On these occasions her three masts whipped violently back and forth as the rigging tightened like harpstrings. But most agonizing for the men were the times when she seemed a huge creature suffocating and gasping for breath, her sides heaving against the strangling pressure.

The whole undertaking was criticized in some circles as being too “audacious.” And perhaps it was. But if it hadn’t been audacious, it wouldn’t have been to Shackleton’s liking. He was, above all, an explorer in the classic mold-utterly self-reliant, romantic, and just a little swashbuckling.”

Then he opened the Bible Queen Alexandra had given them and ripped out the flyleaf and the page containing the Twenty-third Psalm. He also tore out the page from the Book of Job with this verse on it:

They thought of home, naturally, but there was no burning desire to be in civilization for its own sake. Worsley recorded: “Waking on a fine morning I feel a great longing for the smell of dewy wet grass and flowers of a Spring morning in New Zealand or England. One has very few other longings for civilization-good bread and butter, Munich beer, Coromandel rock oysters, apple pie and Devonshire cream are pleasant reminiscences rather than longings.”

This, then, was the Drake Passage, the most dreaded bit of ocean on the globe-and rightly so. Here nature has been given a proving ground on which to demonstrate what she can do if left alone. The results are impressive.”

Thus their plight was naked and terrifying in its simplicity. If they were to get out-they had to get themselves out.”

Unlike the land, where courage and the simple will to endure can often see a man through, the struggle against the sea is an act of

We had seen God in His splendors, heard the text that Nature renders. We had reached the naked soul of man.”